In a remarkable turnaround, NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine on Wednesday said the space agency would consider launching its first Orion mission to the Moon on commercial rockets instead of NASA's own Space Launch System. This caught virtually the entire aerospace world off guard, and represents a bold change from the status quo of Orion as America's spacecraft, and the SLS as America's powerful rocket that will launch it.

The announcement raised a bunch of questions, and we've got some speculative but well-informed answers.

What happened?

During a hearing of the Senate Commerce committee to assess America's future in space, committee chairman Sen. Roger Wicker opened by asking Bridenstine about Exploration Mission-1's ongoing delays. The EM-1 test flight involves sending an uncrewed Orion spacecraft on a three-week mission into lunar orbit, and is regarded as NASA's first step toward returning humans to the Moon. This mission was originally scheduled for late 2017, but it has slipped multiple times, most recently to June 2020. It has also come to light that this date, too, is no longer tenable.

"SLS is struggling to meet its schedule," Bridenstine replied to Wicker's question. "We are now understanding better how difficult this project is, and it’s going to take some additional time. I want to be really clear. I think we as an agency need to stick to our commitment. If we tell you, and others, that we’re going to launch in June of 2020 around the Moon, I think we should launch around the Moon in June of 2020. And I think it can be done. We should consider, as an agency, all options to accomplish that objective."

The only other option at this point is using two large, privately developed heavy lift rockets instead of a single SLS booster. While they are not as powerful as the SLS rocket, these commercial launch vehicles could allow for the mission to happen on schedule.

How will this work?

One heavy-lift rocket would launch a fully fueled upper stage—most likely a Delta Cryogenic Second Stage or the Centaur upper stage currently used on United Launch Alliance rockets. Then, a second heavy-lift rocket would launch an Orion capsule and its service module into orbit, and these two vehicles would dock. The fueled upper stage would then inject Orion into a lunar orbit.

Bridenstine did not name rockets during the hearing, but it seems almost certain that at least one of them would be a Delta IV Heavy, built by United Launch Alliance. NASA used this rocket to launch a version of the Orion spacecraft to an altitude of 3,600km in 2014. Both United Launch Alliance and SpaceX—with its Falcon Heavy rocket—would be invited to bid on the second launch.

This has the makings of a stunning spectacle—imagine a SpaceX Falcon Heavy on one launch pad, and a United Launch Alliance Delta IV Heavy on a pad just a few kilometers away, launching within hours of one another. It would represent the country's two greatest rocket companies coming together for a historic mission—but it remains unclear whether both manufacturers would be involved.

Is this hard?

Coordinating two launches and an orbital rendezvous would require some new technologies and procedures, for sure. "I want to be clear, we do not have right now the ability to dock the Orion crew capsule with anything in orbit," Bridenstine said Wednesday. "So between now and June 2020 we would have to make that a reality."

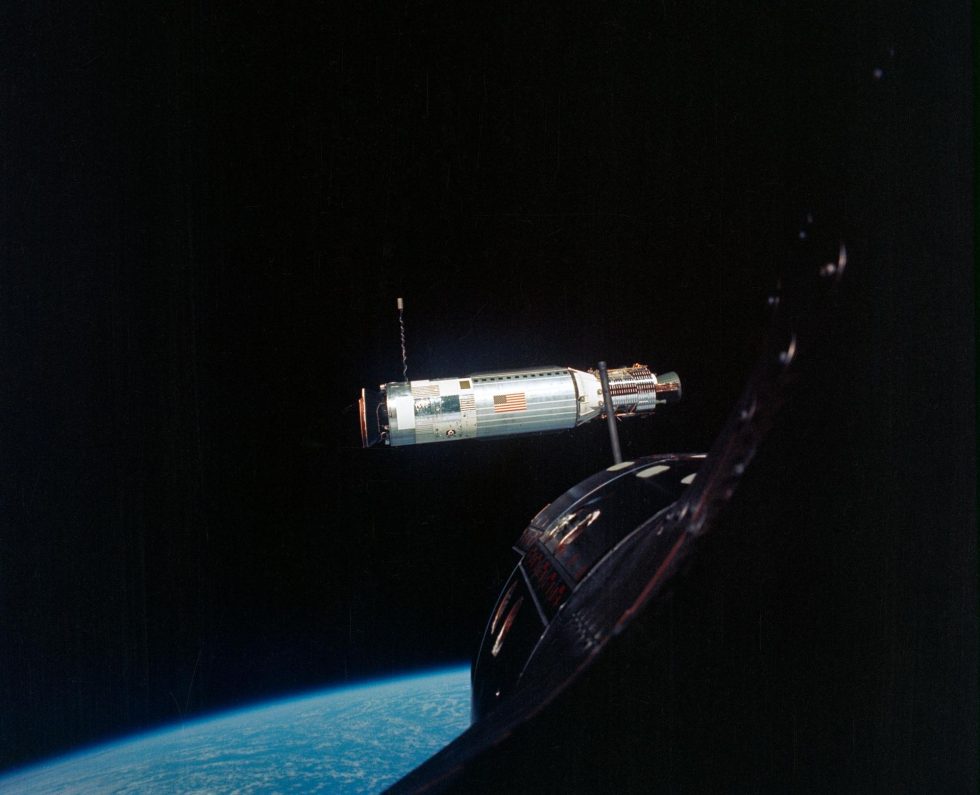

However, NASA has done this kind of thing before. In 1966 the Gemini 10 mission saw an Agena upper stage launched into space, followed by John Young and Michael Collins 100 minutes later in their Gemini capsule. The spacecraft and Agena docked at about 270km above the Earth, and then burned the Agena's engine to go as high as 760km, the highest any altitude above the Earth's surface that any human had reached before.

Time is short, however. If NASA is to launch this mission by June 2020, it must identify the rockets and upper stage it will use, configure Orion to fly on a new rocket, write and test docking procedures, and more. For an agency accustomed to moving relatively slowly, this would require considerable haste.

What happens now?

Bridenstine said NASA engineers are already studying how this can be done. He gave the answer a timeframe of a few weeks, but in an email to employees at the Johnson Space Center in Houston Wednesday, center director Mark Geyer said a preliminary response could come as early as next week.

One big question is how deep support for this plan runs within the agency. It would be relatively easy for mid-level managers to kill this idea, as has happened before (perhaps most famously with President George Bush's Space Exploration Initiative, in 1989 and 1990, as told in Mars Wars). However, a source told Ars that a key figure at NASA headquarters, human spaceflight chief Bill Gerstenmaier, is on board with the plan. This is important, because it means the study should be conducted fairly.

Why has SLS been controversial?

The short answer is that the rocket was largely conceived in the U.S. Senate, so much so that it is derisively been called the "Senate Launch System." The rocket has had an enormous budget (more than $12 billion and counting) and yet it has experienced ongoing delays. And it uses old technology—a similar approach that Apollo used to reach the Moon, with a large, expendable rocket that is neither cost-effective nor sustainable. In fact, the rocket uses surplus Space Shuttle main engines, which were designed to be reusable, but which with SLS will be thrown away after each launch.

Additionally, by funding NASA to develop the SLS rocket, Congress prevented the agency from working on forward-looking technology like in-orbit refueling, propellant depots, space tugs, and other bits that would open up opportunities for a more economical space transportation system, and allow for the use of smaller, reusable rockets like those SpaceX has developed. (The longer story on that can be read here.)

Why did Bridenstine do this?

This was a bold move for a NASA administrator. If this mission happens, and if it is successful, it opens a pathway for commercial rockets to safely send humans to the Moon. In pro forma remarks, Bridenstine said the agency's preference remains using the Space Launch System for Orion crew missions, but it is hard to see the much more costly SLS used in the future if existing commercial launchers can do the same tasks. This means that NASA could carry out its entire lunar program over the next decade or two with commercial rockets that either exist now or will exist in the near future, such as Blue Origin's New Glenn vehicle. Finally, it also opens the door to starting on those cost-saving technologies blocked by SLS, such as low-Earth orbit fueling and multiple-launch missions with smaller rockets.

For this reason, it's really rather remarkable to propose such a concept in the Senate, when there has been such deep institutional support for the SLS rocket for nearly a decade. This was Bridenstine's moment. He made his statement at the witness table Wednesday, without notes, speaking clearly. He has said all along that he wants to lead NASA and help the agency get back to the Moon faster. On Wednesday, he seized the chance to act.

Multiple sources have told Ars that Vice President Mike Pence, who oversees U.S. spaceflight policy, backs this approach. Pence grown tired of the SLS delays, and wants to see NASA getting on with a lunar program. A launch in 2020 would come before the end of President Trump's first term, and would signify that the administration's talk of a human lunar return is not just rhetoric. It would show that the White House is serious about this.

How will Congress react?

President Obama was no great champion for the SLS rocket either—his administration agreed to fund it in return for support for the Boeing and SpaceX commercial crew capsules that will soon carry astronauts to the International Space Station. Since its inception in 2011, the SLS program has therefore found its greatest support in the U.S. Senate, particularly from Alabama's Richard Shelby, who now chairs the powerful Appropriations Committee. The Marshall Space Flight Center, which manages the SLS program for NASA, is located in Alabama.

So far, Shelby is not on board with the plan proposed by Bridenstine. “While I agree that the delay in the SLS launch schedule is unacceptable, I firmly believe that SLS should launch the Orion," he said, in a statement released to Ars.

However, given the backing of Pence and promises of continued funding for SLS, it seems possible that Shelby can be convinced to not outright oppose this plan, or to block it through his power of the purse. Perhaps his price will be that—for this mission, at least—both rockets must be built by United Launch Alliance, which assembles its boosters in Alabama. Regardless, this will be a key dynamic to watch if NASA engineers deem the plan feasible.

What are the rocket companies saying?

SpaceX did not respond to a request for comment about their potential participation in this mission. United Launch Alliance sent Ars this statement:

ULA recognizes the unparalleled capabilities of NASA’s Space Launch System for enabling efficient architectures in Cislunar and Mars exploration. We are proud to have worked collaboratively with The Boeing Company to develop the Interim Cryogenic Propulsion Stage (ICPS) for the first flight of the SLS. If asked, we can provide a description of the capabilities of our launch vehicles for meeting NASA’s needs, but acknowledge that these do not match the super heavy lift performance and mission capabilities provided by SLS for the Exploration Missions proposed by NASA.

It is important to remember that United Launch Alliance is co-owned by Boeing and Lockheed Martin. Boeing is the primary contractor for the SLS rocket. The statement reflects this nuance.

https://arstechnica.com/science/2019/03/what-is-going-on-with-nasas-space-launch-system-rocket/Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Here's why NASA's administrator made such a bold move Wednesday - Ars Technica"

Post a Comment